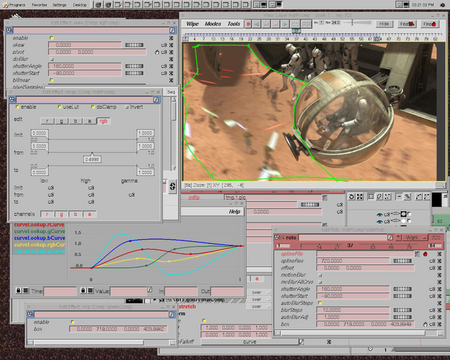

A scene in Star Wars being edited in ILM's proprietary compositing package CompTime. ILM created its own compositor rather than using a commercial package such as Shake or RAYZ. “Linux is increasing the quality of our work, not the quantity”, says Andy Hendrickson, director of research and development. Large amounts of processing power enable more user control. He explains,

ILM made a bold move to undertake their Linux conversion in the midst of a major movie production, switching while work was underway on Episode II. “We thought converting to Linux would be a lot harder than it was”, says Hendrickson. “Linux is so like what we had before. We pushed forward deployment in November 2001 and will finish conversion after Episode II.” During the changeover, ILM is supporting existing SGI IRIX machines and Linux PCs to avoid overwhelming users with too much change. Sequence supervisor Robert Weaver is a technical director on Episode II. Weaver's desk has a Linux PC on the left side and an SGI O2 on the right. Because the Linux desktop is configured to look like the SGI O2, it isn't immediately apparent which screen is which, until Weaver demonstrates the difference in speed. He says,

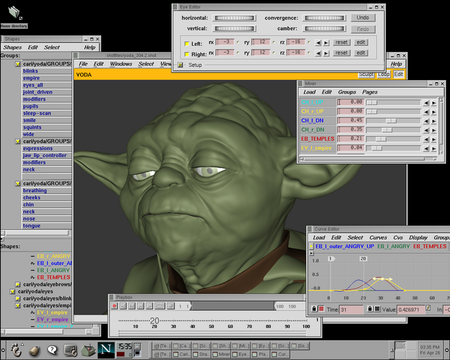

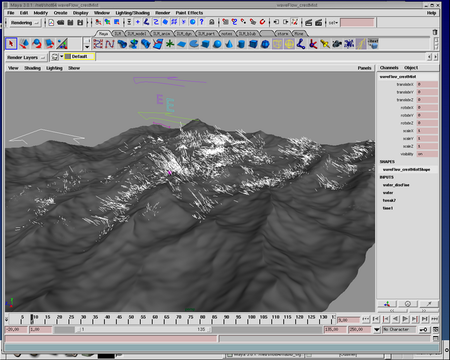

All ILM 3-D particle simulations are done in Alias|Wavefront Maya. “We have, I'd say, 90% of our Maya users on Linux”, says Weaver. “It seems incredibly stable on Linux. I haven't had Maya crash on me in months. I'm evaluating that the correct cycles have been put in. I do that in wireframe mode.” To extend the functionality of Maya, Weaver writes plugins. “Maya makes writing plugins fairly easy. I add stuff to the shelf.” The shelf is a set of plugin tabs visible across the top in Maya. The ocean in Perfect Storm is an example of the effects ILM achieves with Maya plugins. “Our compositing software, CompTime, has been ported to Linux”, notes Weaver. ILM created its own compositor with a plugin architecture for doing motion picture editing rather than choosing a commercial package. Weaver writes compositor plugins, too. “The compositor plugins are in Python”, he notes. “We're a big Python shop...and MEL.” MEL is the Maya scripting language. Maya is considered by ILM a tool best for TDs (technical directors); animators at ILM use SOFTIMAGE. The conversion to Linux triggered a company-wide upgrade from version 3.8 of SOFTIMAGE (on IRIX) to the 4.0 version that recently became available for Linux. In the years since the first Star Wars trilogy, animation software has become capable of greater facial expression. ILM created their own caricature facial animation application that reads and writes SOFTIMAGE scenes directly, not as a plugin. Senior Digital Model Supervisor Geoff Campbell used this software to set up facial expressions for animation in Episode II.  ILM Model Supervisor Geoff Campbell and Animation Director Rob Coleman working on the character animation of Yoda for a scene in Star Wars. “There are 11 muscles in the face that are key to giving a performance”, says Campbell. “I can stretch a face in SOFTIMAGE as much as I want. When I like what I've done, I'll save it as a new shape. At my desk I have a little camera and a mirror I use to view my real facial expressions. You invest a little bit of yourself in each character.” Campbell says an important detail in a character's performance is “eye darts”, the little telling looks that performers give each other when interacting. In Episode II Yoda had eye darts even with his eyes closed. “Linda Bell developed an animation of the eyes while sleeping, that is, the eyes moving in REM sleep under closed eyelids.” “I wanted Yoda to look better than the puppet, to have the lip movements better match the words”, says Campbell. She explains that

The later CG Yoda matches the character in other movies in the series, but he has more exact lip phonemes, with the lips curling to make an “M” or “B” sound, than the puppet could create. For Yoda in Star Wars, ILM used their proprietary facial caricature animation software designed to be file-compatible with SOFTIMAGE. ILM's approach to in-house development includes both proprietary applications such as this and CompTime, and custom plugins for use with commercial pacakges like Maya and SOFTIMAGE. The hair on Yoda is another character feature manipulated with ILM's facial animation software. Because moving individual hairs would be too cumbersome, there are single control hairs that influence the hairs around them. To style Yoda's hair interactively, speed is important. When running ILM's facial animation software on the SGI O2, it took seconds to redraw the screen after each change, and the delay made work difficult. “With Linux we manipulate high-res models in real time in a way we couldn't with our SGI system”, says Campbell. ILM still builds some physical models but mostly for backgrounds or for organic-looking things that can be created easier than with CG. Although ILM doesn't construct many spaceship models anymore, their computerized motion control cameras are still shooting background plates nonstop. R&D Principal Engineer Phil Peterson reports that ILM is about 80% finished with its Linux software conversion. He says, “A team of three people ported over a million lines of code to Linux.” “The biggest issue we had in porting was the compiler and other tools”, says Peterson. “Newer C++ code is fairly dependent on STL.” The gcc 2.96 compiler included with Red Hat didn't support the C++ Standard Template Library (STL), so ILM uses gcc 3.01 instead. Their multiplatform build environment is customized based on Python cooperating with GNU make. ILM had to accommodate some CPU differences, such as floating-point implementation and number precision. “In some cases we hand-optimized in-line assembly to get the most out of Linux”, says Peterson. One issue is how to track memory access per thread in Linux, which handles thread IDs differently from IRIX. Another annoyance is that a floating-point exception isn't allowed to throw a C++ exception (because FP exceptions are asynchronous). In integrating legacy Motif applications, ILM had to overcome some issues with widget differences. “We were using Motif mostly”, says Peterson, “but use FLTK in our latest applications”. ILM made their SGI-based apps look similar on Linux, including the fonts and colors. ILM software projects may incorporate 80 or 90 libraries. For sound ILM uses OSS, but Peterson says they may switch to ALSA. SGI provides the dMedia libraries, but on Linux ILM had to create some of their own media libraries to fill in missing functionality. To play back movies, which at 2k by 1k are more than 27 times larger than typical 320 × 240 PC video, ILM created their own QuickTime-compatible library used in their flipbook player. For the ocean in Perfect Storm, ILM created a Maya plugin with the capability of directing the intensity of particular waves. A key feature of ILM-developed software is user control. “With Linux the increase in speed is what everyone is noticing”, Hendrickson says. He says the speed increase is

George Lucas, who used 400 shots in the original Star Wars, used 2,000 in Episode II. Creating that required three visual effects supervisors, as if doing three shows. “Expect a jump in what we're able to do after Episode II”, says Hendrickson. Источник: www.linuxjournal.com | |

|

| |

| Просмотров: 4323 | Комментарии: 1 | |

| Всего комментариев: 0 | |