Like most studios, D2 was primarily using SGI hardware

running SGI's IRIX variant of UNIX, both on renderfarm servers and

artist workstations. Experiments at D2 with Dante's

Peak in 1996 proved that a move to Linux was feasible.

“The Linux renderfarm came first”, notes D2 Digital Production

and Technology Creative Director Judith Crow. “With

Titanic we were working with a company called

Areté using Renderworld, their ocean-simulation software. It

ran three times faster on our Linux Alphas than on our IRIX SGI

machines.” While the renderfarm paved the way, applications such

as NUKE and Houdini pushed Linux to the desktop.

A compositor is what software artists use for overlaying

moving images, for example, the starship

Enterprise flying past a background matte of a

space station. “Digital Domain has been running NUKE on Linux

since 1997 when it was used extensively on

Titanic”, says Digital Effects Supervisor

Jonathan Egstad. Egstad, along with D2's Bill Spitzak, Paul Van

Camp and Price Pethel received an Academy Award for the NUKE

compositor. “NUKE is essentially a 2-D renderer”, says Egstad. “It is

five or six times faster on Linux than IRIX, but it wasn't until

the beginning of 2001 that the Linux GUI was able to run fast. Back

in 1993, NUKE was the original scanline-based design. It only took

20MB of RAM to render a typical composite instead hundreds of

megabytes.” Later commercial compositor applications, such as

Shake, the popular node-based compositor sold by Apple, have a

similar design. “There are many instances where 2-D can assist in the

workload”, points out Egstad: We can build a complete 3-D scene in NUKE then

refer to that in a 3-D package like Maya and vice versa. A 3-D

scene can be created and rendered in Nuke3, complete with lighting,

texturing and shader support—diffuse, Blinn and Phong are

built-in. There's a complete 3-D subsystem in NUKE. That's a trend

in all 2-D packages. 2-D packages are more and more turning into

3-D packages.

Houdini, a commercial 3-D package of which D2 is a big user,

offers its own integrated compositor called Halo in its latest

version. As with NUKE, it is hierarchy-based in conjunction with

2-D hierarchy. D2 also uses the commercial 3-D packages LightWave

and Maya.

FLTK, the Window Toolkit of

NUKE NUKE version 3 has been in use at D2 since 2001, running on

Linux, IRIX and Windows. D2's first Linux renderfarm was on Digital

Alphas and still gets some use. The NUKE design retained the

keystrokes used in IRIX, so users, especially freelancers working

at D2, wouldn't face a learning curve when moving between operating

systems. “The NUKE interface is deliberately Spartan, designed

more toward feature work”, notes Egstad. “It probably has the

strongest color-correction tools of any major package.” D2's Linux Movies D2 had requests for years to make NUKE into a commercial

product for use by other studios, and the pressure increased after

Apple purchased industry-leader Shake. Studios became concerned

when Apple dallied with announcing future Linux support. “We've founded the D2 Software Company to sell and market

NUKE and other applications that currently exist or don't exist

within the studio”, says Digital Production and Technology VP

Michael Taylor. He continues: We have NUKE evaluation sites out in the field.

We're providing the latest NUKE 3 version that we use internally.

About two years ago when making the decision to do a complete NUKE

rewrite incorporating a 3-D into 2-D model, we considered switching

to Shake, but decided we had a better program.

Taylor says Linux, Windows and IRIX versions will be

available in early 2003. There are no plans yet for Mac OS X.

Pricing starts under $10K US, which is comparable to Shake. For

students, there will be a free-of-charge or inexpensive version,

comparable to the apprentice versions of Maya and Houdini.

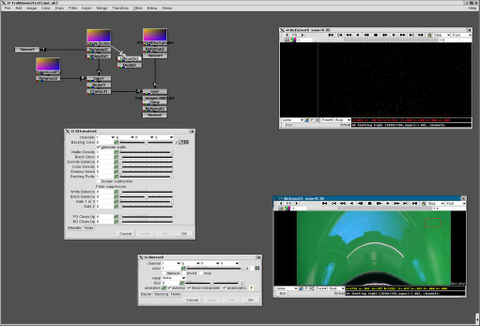

Digital compositor Brian Begun describes working on a scene

in NUKE for Star Trek Nemesis: I'm working on a temp, that's a shot that isn't

finished—isn't ready for film. We have a production intranet for

each show we work on with a web page for each shot. A lot of

artists need to share information. Our job system uses Netscape

with a lot of HTML forms and a server written in Perl. Rather than

files in directories, we have links in directories. We can keep

files in any directory on any drive anywhere without seeing what

drive it is on. This allows our Systems department to juggle our

disk space when necessary and to use it as efficiently as possible,

without affecting production.

Begun walks us through setting up a typical effect in

NUKE—moving the Enterprise across a star

field:

Here's Trek's environment.

We have a predefined list of variables for each show. Let's say I

choose Star Trek SS145A:

$ job trek [sets show variables]

$ shot ss145a [sets job variables]

The cs command switches to my

work directory, in this case work.begun:

$ cs

From here, I can go to an image directory that

contains elements, parts of composite—or the work directory that

contains NUKE scripts and if we do tracking, the in-house Track

scripts. The work directory will contain files for NUKE, Flame,

Track and Elastic Reality (old but cheap software used for roto and

Avid morphing, such as bad frame or wire removal by morphing).

If I need to create my work directory, I use the jsmk

command. Other directories, such as image directories also are

created this way. They contain each green screen, full-resolution

and scaled-down proxy image, previz and temp comp (which gives the

client a rough idea of the shot, but is not necessarily

pretty). The lss command displays files in a more readable format than

ls. For example, instead of looking at files like this:

test.0001.rgb

test.0002.rgb

test.0003.rgb

Typing lss displays files like

this:

test.%04d.rgb 1-3

Before launching NUKE, I change to the NUKE

subdirectory in my work directory:

$ cs

$ cd nuke

$ nuke3

When I launch NUKE, it brings up a GUI window,

and I choose Image®Read®File and then ss145a.wh to load the

foreground (green screen) images. When working on a project, I use

both high-resolution images and quarter-resolution proxy images.

The images are Cineon 10-bit log. NUKE itself will convert

that to 16-bit float. NUKE is capable of displaying up to ten

images in one viewer. By simply entering 1 to 0 on the keyboard, I

can have up to ten views.

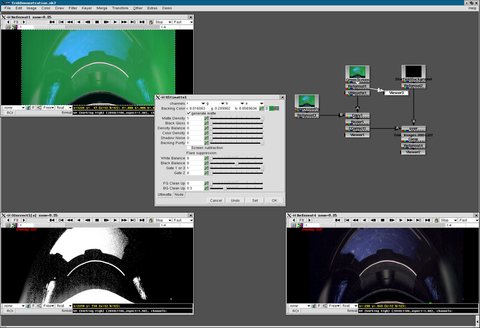

Here's a green screen of a cockpit [see Figure

3]. I bring in the background image of stars. When pulling a green

screen, you'll typically pull three types of mattes. An edge matte

is used to retain all the fine detail present in the photography. A

fill or “innie” is used to fill any holes that may occur due to

green spill or green material in front of the foreground subject.

And, a cleanup or “outtie” matte is used to remove anything that

is supposed to be replaced by the background—such as stage lights.

To pull these mattes, I'll select a “backing color” in

Ultimatte's color picker that best represents the color I want to

remove, and that will give me the best matte. After that, I'll make

any necessary tweaks, including pulling additional mattes where

necessary, or additional cleanup.

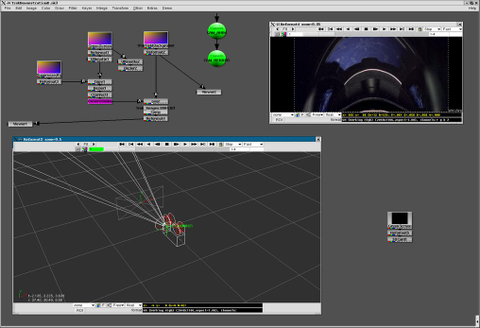

Technical Director Jason Iversen is responsible for energy

beam effects and debris for Star Trek: For ships exploding we use as many practical

effects as possible. Practicals are faster, even though it takes

time to build the model. That may take two guys two months, but it

is three people for four to five months to create a 3-D shot. We

shoot the explosion at 300 fps slo-mo. It's a big task, and still

might not get realism. Some explosions are enhanced with digital

debris using Houdini. Some Enterprise shots

are still real, but not the hull-scraping beauty shots.

As we're talking, one of his SGI machines is being taken away

for use on the renderfarm. At D2, workstations are being upgraded

to dual-Pentium PCs.

Star Trek work at D2 was previously all

done in Houdini on Linux, but most of the Maya artists are on

Windows NT because of Maya plugins not being available on Linux.

“One of the largest sequences we've got is the avalanche sequence,

all in Linux Houdini plus our own internal tool called VoxelB for

doing volumetrics”, notes Iversen. He continues: The avalanche is a huge powdery trail that is

generated in a 3-D sense—not a 2-D cheat. Our voxel compositor

VoxelB is a plugin. All of our tools can take in data from Maya or

Houdini. We often combine those with our fluid dynamics software to

create flowing water.

“Terragen is our terrain-generating program that was used in

Time Machine for planet shots”, says Iversen.

He adds:

We use it for previz and to create the initial

plate for digital painters. Digital actors are all in Maya,

primarily on NT. Our pipeline is based on previz rolling into

production. All artists do precomposites of our work, then get

assigned a compositor to take it to film out.

According to Crow, porting D2's IRIX-based applications to

Linux went rapidly, especially with their compositing software

NUKE. The Linux conversion at D2 happened in stages, first the

renderfarm that performs batch processing of movie effects, then

the desktops where artists work. “When Linux was ready for the

desktop we were eager to adopt it”, says Crow. “As soon as we got

an OS like Linux supporting the features we relied on we were

excited to move to it.”

Источник: www.linuxjournal.com

|